On Monday, May 13, 2024, I left work around 4:00 p.m. and set out towards Gilead with two objectives in mind: the first was to run/hike up Caribou Mountain, and the second was to take a dip in Bog Brook.

The weather wasn’t bad that day, but it was significantly cooler than on the day of my first unplanned dunk in Chapman Brook a week earlier. The day after I devised my brook jumping challenge, the temperature had plummeted from a high in the 70s to more typical seasonal weather in the 50s. Now it was back up to about 60, which seemed tolerable, and I was eager to put another notch in my belt. My plan was to combine an intense workout with a jump in a brook, figuring that if I worked up a good sweat first the cold water would be more inviting.

The Caribou Mountain Trail from Bog Brook was an obvious choice for this because of one particularly attractive feature: a natural swimming hole in Bog Brook, ideally situated at the start/end of the trail.

This may seem an unlikely place to find a nice swimming hole, as the name Bog Brook suggests a swampy, slow-moving stream. Indeed, much of it is, but closer to the 5.6-mile-long brook’s point of origin on Caribou Mountain, it begins as a clear mountain stream.1

Caribou Mountain straddles borders, both natural and manmade. The modern line between Batchelder’s Grant and Mason townships passes right over the summit, and the water that falls there makes its way to the Androscoggin via one of three paths: Wild River by way of Morrison Brook or Mud Brook; Pleasant River via its West Branch; or Bog Brook.

The mountain has quite a storied history, so it’s convenient that with several more brooks and a spring to cover I will have plenty more opportunities to write about it.

Just this past week I was scanning a collection of negatives from the West Bethel area when this image popped up on my screen. When my friend Carolyn Hardy, one of the Museums of the Bethel Historical Society’s board members and volunteers, arrived to take over the project, I showed her the image and she excitedly produced a handwritten history of the little camp—which was built near the top of Caribou Mountain in 1908—from her grandmother’s records which she has been digitizing.

Needless to say, we’ll be picking up the story of Camp Caribou on future visits to the mountain, but for now I want to give a little history from an even earlier era.

The Bog Brook side is an appropriate place to dive into the history, since this is the direction from which the earliest ascents seem to have been made. This is unsurprising, as before the road was developed through Evans Notch there wasn’t much for convenient access from the westerly direction.

Cook and Pychowska

As with many other mountains in the area, it’s likely that the first people to climb Caribou were local youth, hunters, and berry pickers. It’s obvious that plenty of people had visited the top by the 1870s, as the view is described in a few early publications, and there were logging operations conducted here for which roads were apparently built nearly all the way to the summit.

But it was not until enthusiasts affiliated with the White Mountain Club of Portland (1873-1880s) and the Appalachian Mountain Club (founded 1876) began systematically exploring the White Mountains and writing up their experiences that many detailed accounts were published of how these peaks were actually reached.

The December 1883 issue of Appalachia magazine, the journal of the AMC, included a report by Eugene B. Cook who summited Caribou in 1877 in the company of his niece Marian Pychowska. Pychowska and her mother Lucia Cook Pychowska were among a handful of pioneering women who helped to map the White Mountains and were the first to reach numerous peaks.

Cook’s report goes as follows:

The rocky crest of Mt. Caribou, seen from Shelburne Moriah, gave promise of an excellent outlook. As the wide-stretching forests of the Wild River valley did not seem a promising way of approach, a reconnaissance was made by the writer down the Androscoggin valley. The best line of attack from Shelburne was found to be via Gilead. About two miles therefrom, on the way to West Bethel, a road starts off to the right, passing through a gate, just beyond which stands a schoolhouse. A tolerable road leads thence to the farms scattered along Bog Meadow. The road passes over Bog Meadow, a portion of which consists of a chain of narrow, connected fields devoted to the production of hay.

Farther along, some rather desolate farms are passed, after which the road goes into the woods and follows a stream, on its western side. A bridge is seen before long, near which are two or more houses, — one being a rather elegant cottage, unoccupied whenever the narrator has chanced to pass it.

Two routes are here at one’s choice. One can either continue by the wood-road which keeps along the western side of the stream, follow the road to its end, and then ascend a ridge which leads up to a point not far from the top of Mt. Caribou; or one can cross the bridge and follow a logging-road that keeps on the eastern and southern side of the stream, and ends only a short distance below the summit. This latter route is preferable, because the natural line of ascent brings one out directly on the summit. By the other approach, when the top of the ridge is reached, it is necessary to cross a hollow which separates “Wrong Mountain” from the highest head of Caribou. From West Bethel there seems to be an easy approach, by means of a high-road and a wood-road branching therefrom, which leads below the east side of the mountain.

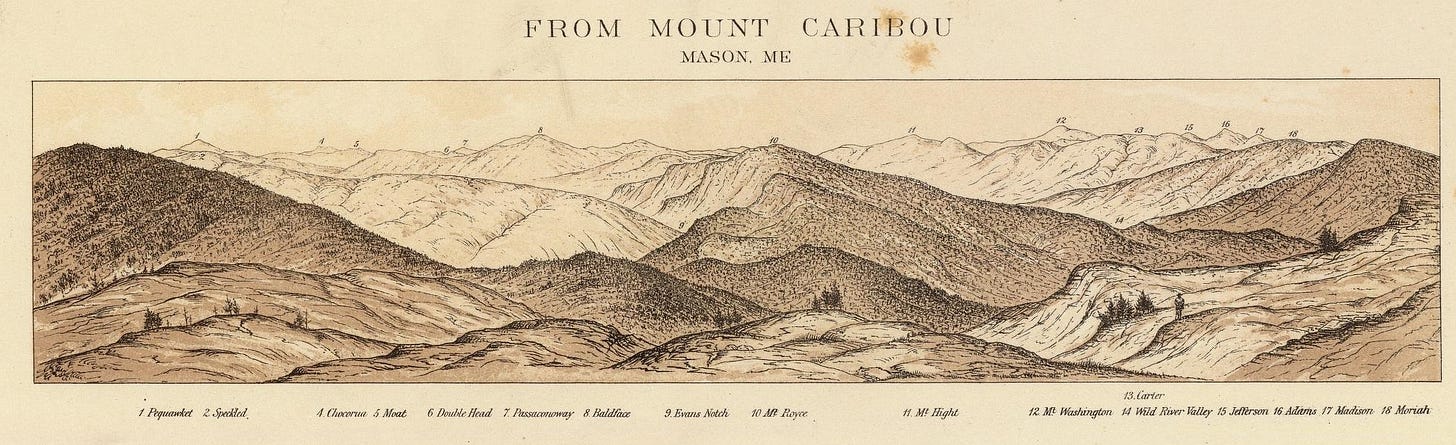

In Professor Hitchcock’s “Geology of New Hampshire” is an interesting plate, giving outlines of some of the mountains seen from Mt. Caribou.

The Moriah and Carter ranges, from Caribou, appear finely over the valley of the Wild River. Speckled Mountain, Mt. Royce, and Baldface Mountain, invite one to continue one’s walk along the whole line. Many lakes in Maine offer their bright mirrors to beautify the landscape. The top of Mt. Caribou is in possession of rocks and moss, is rather long and narrow, and its surface is undulating. From Shelburne Moriah this waving line is well seen; but from Mt. Royce the top of Caribou seems a fantastic pile of rock, suggestive of Mts. Crawford and Chocorua. In the season, excellent blueberries are to be found on Caribou, and its crest is adorned with the Alpine silver-chickweed.

The writer has ascended Caribou four times. In 1877, on a very warm day, my niece, Miss Pychowska, and I, made the ascent. We left Gilead Station at half-past nine, A.M., reached the bridge that has been mentioned at eleven o’clock, and stood on the summit of Mt. Caribou at seven minutes before one. In coming down, the bridge was reached in an hour and twelve minutes, the school-house in forty-eight minutes more, and the railway station at Gilead in thirty-seven minutes, — the whole time from the summit being two hours and thirty-seven minutes. The time taken in making the ascent was three hours and twenty-three minutes from Gilead Station.

It’s always difficult to untangle a description such as this, given how much the roads have changed, and the imprecise physical geography of older maps. Before the U.S. Geological Survey began systematically collecting data and publishing topographic maps in the mid-1880s, cartographers often relied on a variety of local knowledge and survey data of decidedly mixed quality. These maps are invaluable for their information on roads and settlements, but are particularly impressionistic in their depiction of mountains, ranges, ponds, and streams.

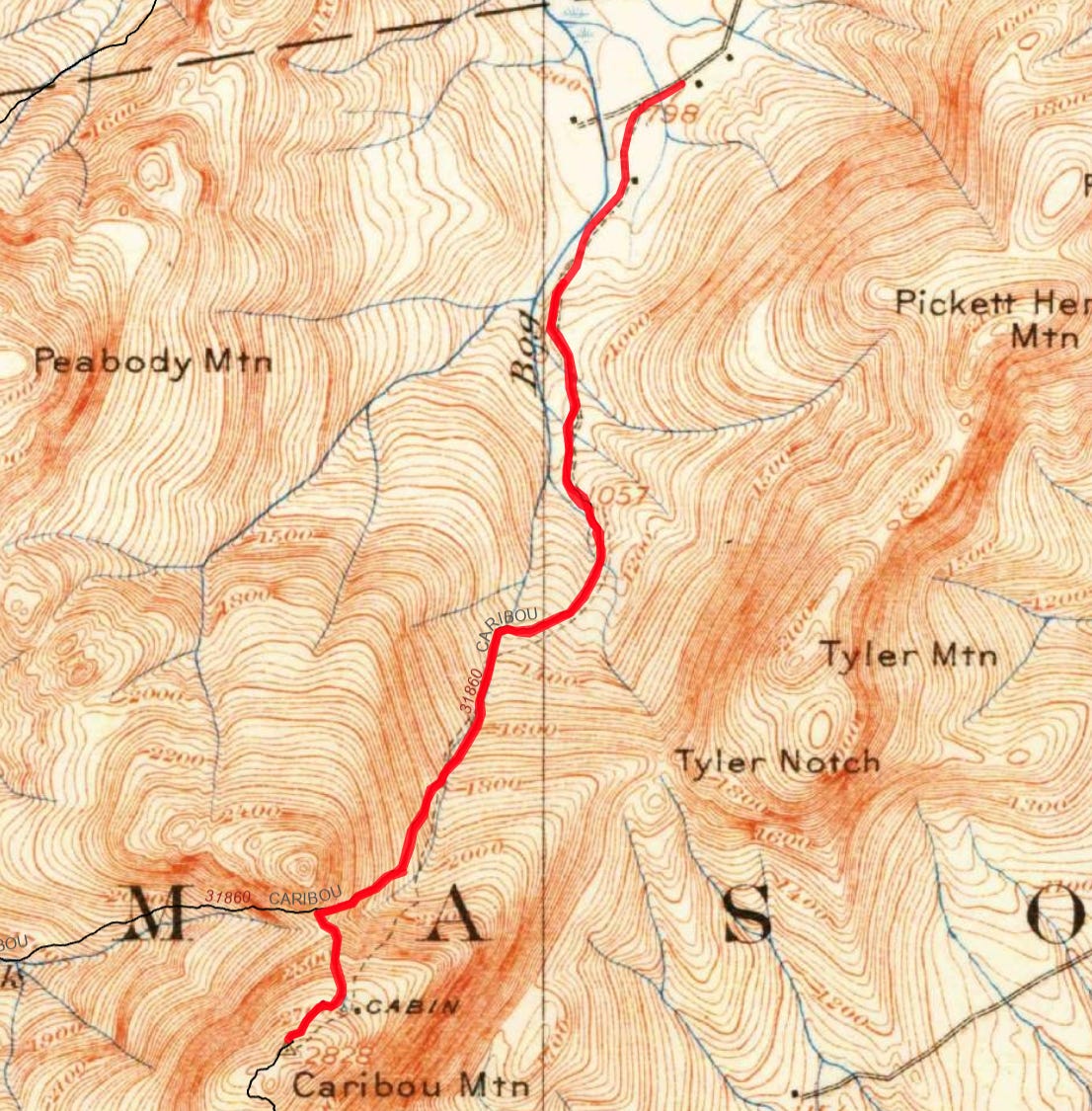

A useful bridge between nineteenth-century and modern maps is the collection of historic USGS topographical maps available through the topoView service. The earliest available for this area is the Bethel Quadrangle from 1914, which already shows a trail to the summit. These maps are geographically accurate enough that it is possibly to overlay them on modern maps, but also show some no longer extant houses and other features we can match with the earlier maps.

I had originally assumed that Cook would have approached the base of the mountain by starting in the Bog Road. However, the road which “starts off to the right” was about two miles or a thirty-seven minute walk from the railroad station in Gilead (highlight 1 on 1880 map above). This must not be the Bog Road, which would be another two miles on, but another road that once went in just after the main road crosses Bog Brook. There is still today a dirt road that begins here, perhaps close to the location of the old road.

This also means that the schoolhouse mentioned by Cook would be the one that stood at the corner here (highlight 2 on 1880 map, and labeled Peabody School in 1883), rather than the schoolhouse at the end of today’s Bog Road (circled in red—now the site of a gravel pit). Although the 1880 map does not show it, it must have been possible to connect through on this road beyond the homestead of P. B. Heath to the Bog Road (at highlight 3) to reach “the farms scattered along Bog Meadow.”

There should have been at least two stream crossings, but the bridge mentioned I take to be the one at highlight 4, since this would put one “on the eastern and southern side of the stream.”

The Trail Today

I have my own fairly lengthy history with Bog Brook and Caribou Mountain. One of my best friends lived on the Bog Road growing up and we used to go to the swimming hole at the base of the trail fairly often. I can vaguely recall some earlier hikes of which I have no records, but in the past six years, I have hiked it at least ten times. (Once in 2018, once in 2021, twice in 2022, and three times each in 2023 and 2024.) Of these, five were from the Evans Notch side on the Caribou-Mud Brook Loop, and five were from the Bog Road.

The Bog Brook side is the only way of accessing Caribou Mountain when the Evans Notch Road is closed. During the winter and shoulder season the end of the Bog Road may also be gated after Pooh Corner Farm, as it was on May 13 last year. I parked my car in front of the gate and ran in the road. This added about 3/4 of a mile to the beginning and end, but was a good way to warm up before starting the climb.

The dirt road dead ends at a gate that is closed year round. There are just a few places to park here, but I’ve never seen more than a handful of cars. On the west side of the road there is a short path that leads to a picnic area and the swimming hole on Bog Brook. The Caribou trail starts by walking around the gate and continuing on up the old road.

The modern trail was first built on top of these same old logging roads followed by Cook and Pychowksa and has changed remarkably little over the past 100 years. Overlaying my GPS track on the 1914 USGS map, we see only a few small variances.

The trail hews pretty close to Bog Brook for most of the way, crossing back and forth over the main stem and its tributaries several times.

The entirety of the trail is within the White Mountain National Forest, but after about two miles you cross the boundary into the Caribou-Speckled Mountain Wilderness.

This is a specially designated area within the White Mountain National Forest that is more restricted. Wilderness areas prohibit all logging, mining, and motorized vehicle use.

The next third of a mile beyond this point appears to be the only real change from the former course of the trail. As you can see on the 1914 map, the trail formerly diverged up the left side of the valley here and ascended directly towards the site of the Camp Caribou cabin below the peak. It now follows it all the way up to the col between between Caribou Mountain and Gammon Mountain (which I take to be the “Wrong Mountain” mentioned by Cook).

At the col it meets with the trail that follows Morrison Brook up from Evans Notch. You then turn left and ascend another fairly steep half mile to the summit.

A Vastness of Vacciniums

What first strikes everyone who reaches the peak of Caribou is of course its gorgeous 365-degree views from the expansive top.

I think only a few hikes in the area of comparable height and distance can rival it—Rumford Whitecap and Sunday River Whitecap come to mind.

But Caribou also shares one other notable feature with the two local Whitecaps: its abundance of blueberries, bilberries, huckleberries, cranberries, and the like (all of which belong to the genus vaccinium).

In a July 11, 1970, article in the Lewiston Evening Journal, Edith Labbie wrote:

On the crest is an acre of flat land. Amid a carpet of gray lichen, ruby red cranberries may be found in the fall.

As I remember it, it was in this same location that I tasted my first mountain cranberries—or lingonberries, as they are more properly called. On a hike with my cousins Keith and Cindi on September 4, 2021, someone in our party used a phone app to identify what we were pretty sure were edible berries. There were just enough of them for each of us to have a small taste.2

Old newspaper articles are full of references to people collecting these tart treats, but I tend to hear much less about mountain cranberry picking as compared to blueberry picking these days. Now that I recognize them, however, they have become one of my favorite trail snacks. They seem to evade me when I deliberately seek them out, but when I find them I never pass up the opportunity.

A couple years ago I was on East Royce Mountain, just across the valley from Caribou, and happened upon so many that I managed to collect a whole pint container full. Having no other container with me, I emptied out the water bladder from my running vest and used that to carry them down.

Two Down, Four Hundred and Some Odd to Go

There were obviously no berries to be found in May, but the views from the top were as resplendent as ever. I paused to take a few photos of the view and an obligatory summit-selfie of me and the pooch, and then we were on our way again.

I made it up from my car and back as far as the trailhead (about 6.25 miles with 2,000 feet of elevation gain) in an hour and 22 minutes, a time I was pretty happy with considering I had only just gotten back into the swing of trail running after the winter. By the time I reached the bottom I was, as predicted, more than ready for a cold dip in the brook, after which I walked the remaining 3/4 of a mile back to my car.

Streams bagged this trip: 1

Total streams bagged as of May 13, 2024: 2

Incidentally, Bog Brook is one of the most common brook names in the Androscoggin River watershed. I believe there are at least 10 of them, plus a Bogg Brook, an Edmunds Bog Brook, a Moose Bog Brook, a Beaver Bog Brook, and a South Bog Stream.

Mom doesn’t remember this, but I’m nearly certain it was here, if not on that hike then perhaps when we climbed it in 2018.

This is excellent, Will. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks, Will, for this great writing and exploring!